- Earth’s magnetic north pole keeps moving as our planet’s magnetic field changes.

- It has moved so much, in fact, that scientists issued an early update to the World Magnetic Model (WMM) in February.

- The WMM informs everything from Google Maps to the US Department of Defense’s navigation systems.

- The latest version of the WMM, published December 10, shows that magnetic north is still moving towards Siberia from eastern Canada.

- Visit Business Insider’s homepage for more stories.

Earth’s magnetic north pole has been leading scientists on something of a wild goose chase.

Over the last 40 years, the spot toward which all our compasses point has moved by an average of about 30 miles per year. In September, magnetic north aligned briefly with geographic north (where all the lines of longitude converge at the North Pole) as it passed over the Prime Meridian.

But then it kept moving, skittering from its previous location in Nunavut, Canada towards Siberia.

“Magnetic north has spent the last 350 years wandering around the same part of Canada,” Ciaran Beggan, a scientist from the British Geological Survey (BGS), told Business Insider. “But since the 1980s, the rate it was moving jumped from 10 kilometers [6.2 miles] per year to 50 kilometers [31 miles].”

Beggan is part of a group of scientists who track the errant pole from year to year. Their work informs the World Magnetic Model (WMM), a map of the planet's magnetic field.

According to the most recent update of the WMM, magnetic north is still zooming along, though its speed has decreased a bit, to 24.8 miles per year.

"By 2040, all compasses will probably point eastward of true north," Beggan said, adding that magnetic north's march toward northern Russia is far from over.

Magnetic north is crucial for navigation systems

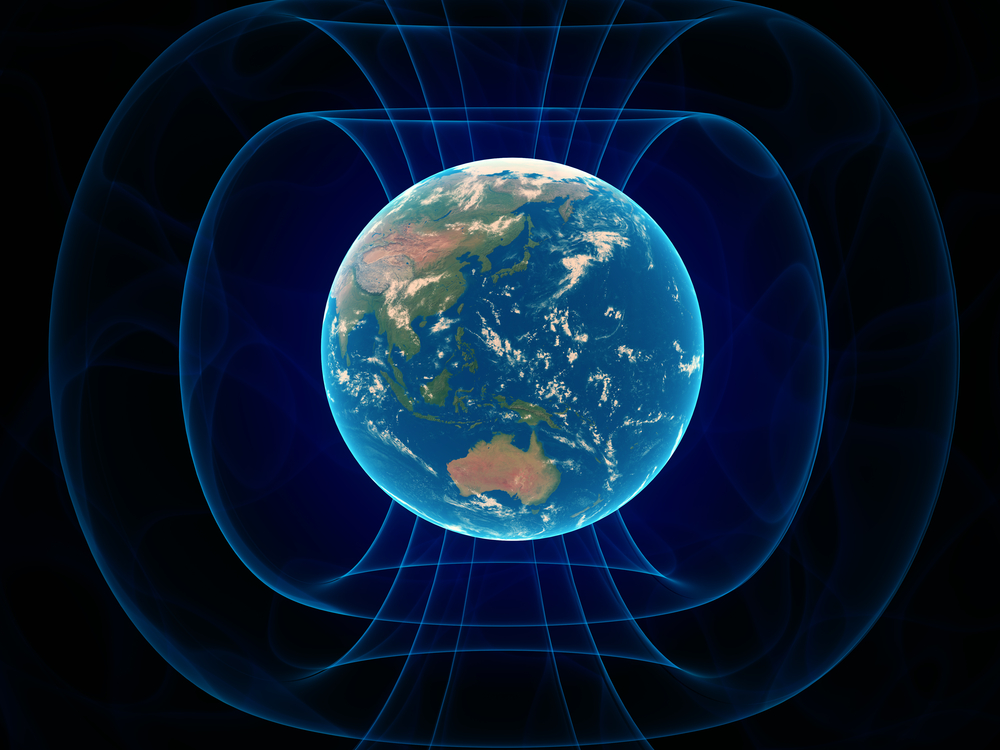

Earth's magnetic field is a sheath of geomagnetic energy that shields the planet from deadly and destructive solar radiation. Without it, solar winds could strip Earth of its oceans and atmosphere.

But the magnetic field and its poles aren't static. Since scientists discovered the magnetic north pole's existence in 1831, it has moved 1,400 miles. Magnetic south, however, hasn't moved at all in the last century, Beggan said.

Keeping tabs on changes in the magnetic field is imperative for European and American militaries, since their navigation systems rely on it. So, too, do GPS apps and commercial airlines.

That's why every five years, BGS and NOAA release an updated World Magnetic Model.

The WMM isn't a static snapshot of what the Earth's magnetic field looks like every five years. Rather, it's a list of numbers that allows devices and navigators to calculate what the magnetic field will look like anywhere on Earth at any time during the five years after the model was published. The WMM was updated for 2015 and scheduled for another update for 2020.

Recently, however, magnetic north's gambol around the Arctic accelerated so much that the movement made the WMM inaccurate.

Mapping a moving field

The magnetic north pole's uncharacteristically fast movement over the last five years introduced errors into the 2015 model that became big enough to worry the US military.

"We asked the US Department of Defense if they wanted an early update, and they said yes," Beggan said. "UK ministry defense wasn't bothered either way."

So the WMM got an unprecedented "out-of-cycle update" in February. Then the scheduled update for 2020 was released on December 10.

According to Beggan, however, a discrepancy between the WMM and the movement of the magnetic pole doesn't affect us as much as one might think.

"Compasses and GPS will work as usual; there's no need for anyone to worry about any disturbance to daily life," he said in a press release.

It's really only directional drilling companies and the Department of Defense that need a more up-to-date, accurate model, he added. That's because drilling companies use compasses and the magnetic field to guide drill bits. The DOD, meanwhile, wants as much precision as possible for navigation systems on its planes, submarines, and parachutes.

Tugged by changes in the Earth's core

One theory about why the planet's magnetic field keeps shifting is that geomagnetic pulses in the planet's core throw the field into whack.

Earth's magnetic field exists thanks to swirling liquid nickel and iron in the planet's outer core, 1,800 miles beneath the surface. Anchored by the north and south magnetic poles (which tend to shift and even reverse every million years or so), the field waxes and wanes in strength, undulating based on what's going on in the core.

"The outer core's liquid iron is hot and runny, as runny as water is on Earth's surface," Beggan said.

Periodic and sometimes random changes in the distribution of the turbulent liquid metal in the Earth's core can cause idiosyncrasies in the magnetic field. If you imagine the magnetic field as a series of rubber bands that thread through the magnetic poles and the Earth's core, changes in the core essentially tug on different rubber bands in various places.

Those geomagnetic tugs influence the north magnetic pole's migration and can cause it to veer wildly from its position.

But the turbulence of the outer core can make it hard for researchers like Beggan to predict how it might affect the magnetic field in the future. In the next 10 to 20 years, he said, we might see magnetic north continue toward Siberia, or it could stop moving or go back the other way.

A weakening magnetic field

Another theory about why magnetic north has become nomadic is that our magnetic field is undergoing a period of weakening.

Justin Revenaugh, a seismologist from the University of Minnesota, previously told Business Insider that such weakening can accompany a process in which magnetic north and south switch places.

That has happened several times in Earth's history; the latest reversal was 780,000 years ago.

When such swaps are occurring, the magnetic field drops to about 30% of its full strength, Revenaugh said. Magnetic north loses its strength during these times too, according to Beggan, and sometimes disappears completely for a time. If the pole were to vanish, compasses would instead point to local magnetic north poles that form all over the planet.

Then about a millennium later, those local poles would reform into one big magnetic north pole as the reversal process progressed.

But a full reversal takes so long that people on Earth would be mostly unaffected. According to a paper published in August, the last swap took 22,000 years to be fully complete.

"So you'd never know if you were living through a reversal, really," Beggan said.